I had the great pleasure of attending ResearchEDBrum as a speaker again this year. This time, the event’s amazing organiser, Claire Stoneman (@stoneman_claire) asked if I would be interested in presenting a session on an evidence-informed approach to my pastoral role; of course, I said yes. Within minutes, a nauseating realisation washed over me: I do not have one.

I have been banging the drum in favour of research and evidence informed practice in education for some years now, zealously encouraging my colleagues to engage with evidence through emails, INSET sessions, invites to rED events and so on. My English departmental colleagues and I have reworked our schemes of work to incorporate interleaving, spaced practice, and the testing effect. I have shared links to Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction with just about everyone, and have adapted my own classroom practice in response to reading it. I have stripped back my classroom displays, employed retrieval practice in most lessons, and attempted some dual coding on my board. And yet, when it comes to my role as Head of Year, nothing is based on research.

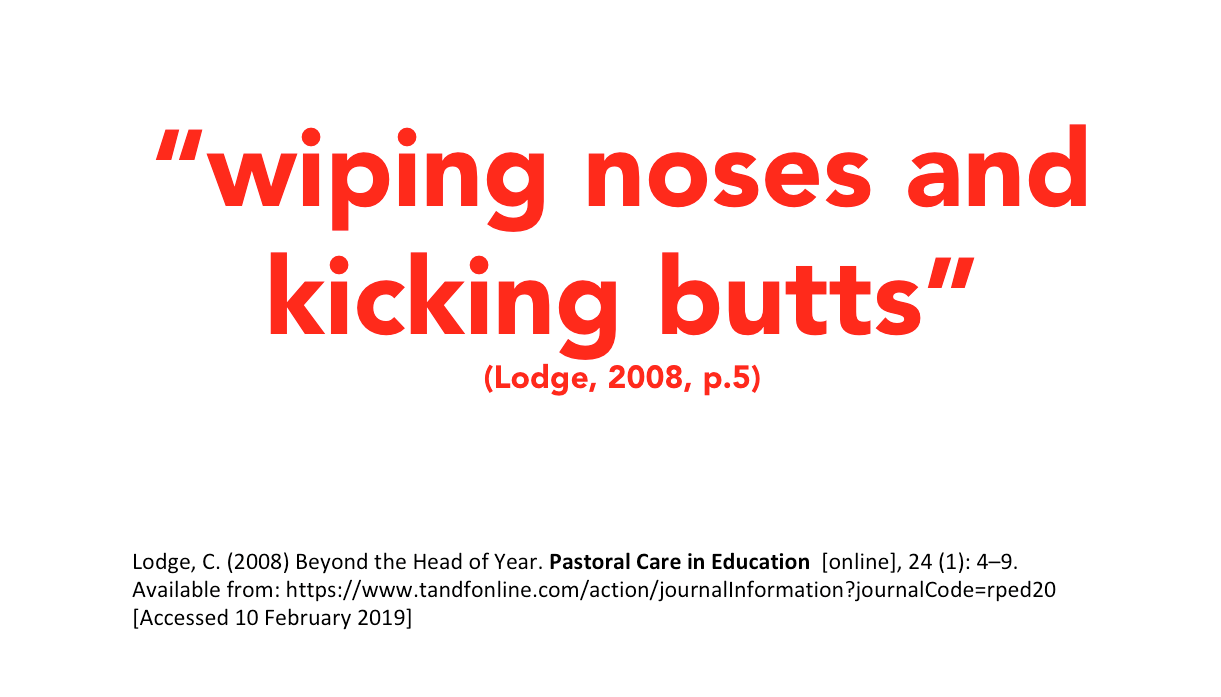

By the very nature of pastoral work, much of what we do is reactive and often ad hoc. It is, perhaps, instinctive. We deal with issues in the moment, and try to pick up the pieces as we go. But this somehow didn’t feel good enough. I felt that there probably ought to be a more robust approach, and was certain that there must be a solid body of literature for Heads of Year and pastoral leaders to consult.

So I looked.

And looked.

I found a couple of How to … type handbooks, one of which claimed to be a “post-modern approach” to the practice of pastoral care. But nothing that struck me as being especially rigorous, academic, or robust. Nothing with an extensive reference list; nothing pointing to a literature review.

But then I came across the journal Pastoral Care in Education, which led me to the National Association for Pastoral Care in Education (NAPCE). The journal is peer reviewed and, despite having a clear leaning towards a social constructivist approach to schooling, contains a range of papers covering a wide array of topics. Some of the papers are free to access. With a rising number of issues I face being due to children’s use of social media and messaging apps, of particular immediate interest to me was a piece titled ‘Cyberbullying bystanders and moral engagement: a psychosocial analysis for pastoral care‘. Searching the journal’s database for the key term ‘bullying’ returns over 1300 results.

But then I came across the journal Pastoral Care in Education, which led me to the National Association for Pastoral Care in Education (NAPCE). The journal is peer reviewed and, despite having a clear leaning towards a social constructivist approach to schooling, contains a range of papers covering a wide array of topics. Some of the papers are free to access. With a rising number of issues I face being due to children’s use of social media and messaging apps, of particular immediate interest to me was a piece titled ‘Cyberbullying bystanders and moral engagement: a psychosocial analysis for pastoral care‘. Searching the journal’s database for the key term ‘bullying’ returns over 1300 results.

Clearly, here is a resource of great potential for Heads of Year and pastoral leaders. Whilst not all articles are free access, the journal’s papers can be found through the Chartered College of Teaching journal access.

The role of Head of Year incorporates many strands, each of which could no doubt call upon a wealth of field specific research and, perhaps, even empirical evidence.  It is interesting to note that, in all our work as teachers, there is probably only one area with a specific, nationally mandated body of literature that all teachers must be familiar with: safeguarding. With statutory updates, safeguarding policy and practice rests upon specific cases, such as Victoria Climbié and Baby Peter, and responds to changing understanding of issues such as county lines. Whilst it is absolutely right that safeguarding commands such high priority for our attention and mandatory CPD, it is telling that it remains the only area of our work with an agreed body of knowledge, and established protocols for action. No other area in teaching, or in school work, carries such certainty.

It is interesting to note that, in all our work as teachers, there is probably only one area with a specific, nationally mandated body of literature that all teachers must be familiar with: safeguarding. With statutory updates, safeguarding policy and practice rests upon specific cases, such as Victoria Climbié and Baby Peter, and responds to changing understanding of issues such as county lines. Whilst it is absolutely right that safeguarding commands such high priority for our attention and mandatory CPD, it is telling that it remains the only area of our work with an agreed body of knowledge, and established protocols for action. No other area in teaching, or in school work, carries such certainty.

For those who might wish teaching to be considered a profession, or to be regarded with the esteem of, say medicine, the notion of taking an ad hoc approach to pastoral care must only seem foolish. Developing an empirical, evidence informed response must surely represent a necessary step forward.

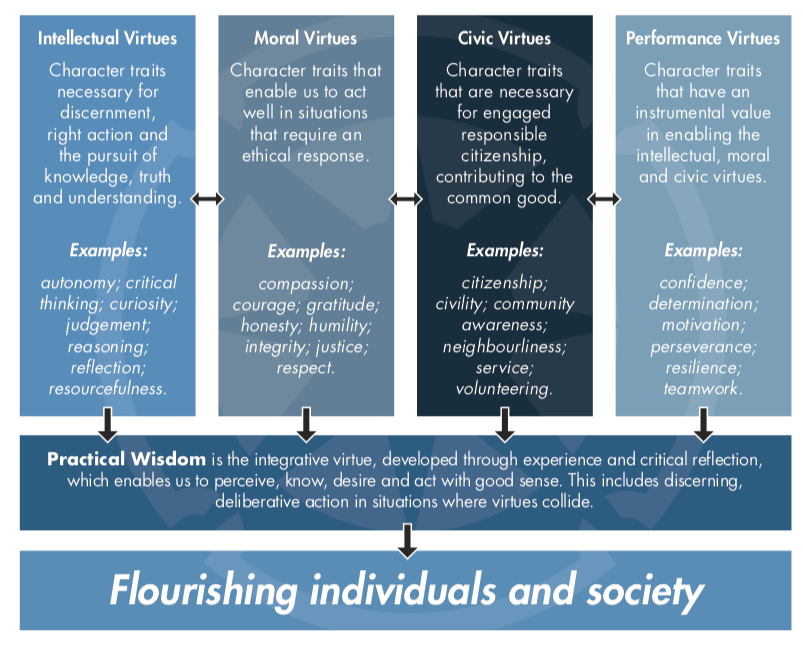

One area of research which seems like a good fit for pastoral care is that of character education. There are those who may see character education as yet another nebulous generic skill, and I’m incredibly disappointed in the list that Damian Hinds gives as his “five foundations for building character“. However, I would much rather look to the work of the Jubilee Centre at the University of Birmingham (@jubileecentre1) for a better idea of what might constitute character education. Furthermore, with the current focus on curriculum, I see the Jubilee Centre’s ideas as giving the potential grounding for character education as a more concrete curriculum artefact – a subject that can be taught.

By way of example, my colleague Jo Owens (@joanneowens) and I recently did some work with our Year 9 students on how it might be argued that Atticus Finch is presented as an idealised virtuous character, finding examples from To Kill A Mockingbird of when Finch demonstrates the various virtues from the Jubilee Centre’s lists.

If it is the case that we can conceive of the pastoral as curriculum artefacts that can be taught, then perhaps we can make explicit use of things such as cognitive load theory and Rosenshine after all. Certainly, if we see PSHE, for example, as a timetabled lesson, then whatever we choose to incorporate can be handled just as any other subject discipline knowledge. It is easy to envisage the use of, say, knowledge organisers and quizzes to ensure that any pastoral knowledge that we deem relevant and important is moved into long-term memory.

As Head of Year, I am also responsible for weekly assemblies. In my setting, these are fairly easy to organise – the work is done for me by dint of the Book of Common Prayer! But here is another opportunity for me to make explicit those aspects of the pastoral that we might deem to be important. I can recall during my B.Ed being taught about the ‘hidden curriculum’ – all those aspects of pupil learning that we do not, or cannot, plan for. I wonder if we might, in fact, be able to unhide these aspects, to reveal them through a determined, conscious and deliberate process of identifying the specific pastoral knowledge we wish our students to learn, and explicitly teaching them.

And finally (for now), we must not ignore the symbiotic relationship between the pastoral and the academic. It is very tempting to suggest that, in order to succeed, students must be happy. But it is in fact the case that academic success can bring happiness.

It is interesting that Project Follow Through found such large positive effects for Direct Instruction, and other academic programmes, upon non-academic measures of problem-solving and wellbeing, whilst those programmes which were designed to specifically target problem-solving and wellbeing had zero, or at worst, negative impacts on those very measures.

So, in order to move towards a research informed approach to the pastoral, I suggest that we need to do the following:

- Develop dynamic pastoral policies which make reference to peer-reviewed material and that can be adapted in response to new findings;

- Consider the academic and the pastoral in symbiosis;

- Consider the pastoral as curriculum, and teach it explicitly.

In a future post, I will consider how Foucault’s reflections on the Panopticon and Orwell’s dark prophecy of Big Brother, might be put to positive use in the act of (as Biesta puts it) socialisation and subjectification.

But then I came across the journal

But then I came across the journal  It is interesting to note that, in all our work as teachers, there is probably only one area with a specific, nationally mandated body of literature that all teachers must be familiar with: safeguarding. With statutory updates, safeguarding policy and practice rests upon specific cases, such as Victoria Climbié

It is interesting to note that, in all our work as teachers, there is probably only one area with a specific, nationally mandated body of literature that all teachers must be familiar with: safeguarding. With statutory updates, safeguarding policy and practice rests upon specific cases, such as Victoria Climbié